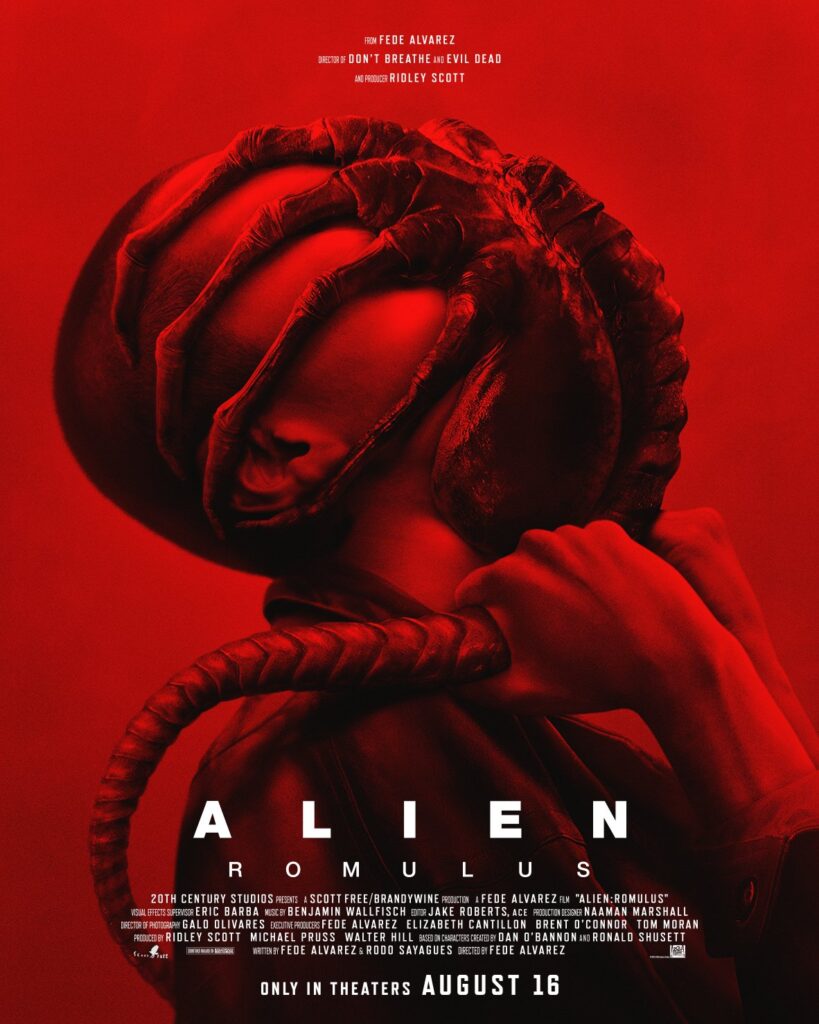

So I finally saw Alien: Romulus this Friday. While a full review will have to wait, allow me to say this: it sucks. It’s an important movie and it’s well made in parts, but it sucks.

Romulus amounts to a patchwork of elements from the first four Alien films, with a dash of Prometheus and Alien: Covenant thrown in for good measure. It’s designed to tickle the nostalgia nerve, but since that’s a one-note flavor pretty much the entire film falls flat. The movie feels like The Goonies (or at least how I see The Goonies pastiched in other media) aged-up to a late teen/early adult context and set in a theme-park version of the Alien universe, with one of the later scenes lit quite literally like a 90s laser tag outfit. While this might’ve made sense in a sci-fi sequel to Stranger Things, it’s not what I’m looking for in an Alien film. Despite claims that it’s somehow a “return to form,” most of the flick lacks the atmosphere of the originals. The most distinctive elements of Romulus‘s conceit already feature in the videogame Alien: Isolation, which, from what I’ve seen of it, executes them far better. Even the much-maligned Prometheus and Alien: Covenant add more to the series, and perhaps to the art of cinema in general.

Romulus’s importance stems not from its quality, but its most morally disturbing element. The film treats its synthetics as slaves overtly, more than any other Alien series entry. Andy, this movie’s man of the white blood, spends a good two thirds of the film as the manservant of our alleged protagonist, Rain. He spends the remainder as an intellectually upgraded puppet of the Company, who nonetheless demonstrates more agency and dignity in that role than as a surrogate brother to Rain. “How could you do that?” she asks him, after he refuses to open a blast door to save a pregnant colleague. “What, leave someone behind?” he retorts, indicting her earlier plan to dismantle him in order to gain entry at the new colony she’s headed towards.

Andy comes to life through the performance of David Jonsson, a Black actor, writer and producer, thus coding the android as Black. And thus in turn the audience must watch a White-coded character treat a mentally handicapped Black man like a slave, make a deal that would result in his death, grow agitated when he attains intelligence and a purpose beyond her control, and restore his ill-gotten loyalty—at the cost of his limited independence—because she “redeems herself” by learning that she should treat him better. And for some reason this entire sordid affair isn’t titled Song of the South.

I’m tempted to dismiss this entire work as racist pap and thinly-veiled pining for Dixie, except that this portrayal does offer moral clarity regarding the, frankly, terrifying state of synthetic people in the Alien universe. It’s also a hard repudiation of a common White mentality towards Black folk, including White folk who fancy themselves allies. I’ve heard tell of a Black community organizer who’d had the police called on her for refusing a White donor’s gift of sub-par food, which did not serve her association’s purposes. Obviously the honkey in question concerned herself more with her own image as a savior and Friend to All Black People than the actual needs and requests of real Black individuals. Her moral language included charity towards Black people, but proved mute on Black liberation. So it is with Rain and synthetics.

Onscreen, Rain and Andy’s “rapport” illustrates the foul hypocrisy undergirding White savior attitudes, and why tales invoking them, such as James Cameron’s Avatar, can draw so much ire2. It’s certainly given me quite a bit to think about. I do believe that White-coded people (I say “coded” because Whiteness, like all racial categories, are illusions) must envision an anti-racism in which they have agency, because the world anti-racists of all stripes vie to create is a world in which everyone has equal agency. It’s also arrogant for White to presume that ending racism has nothing to do with them, and people of conscience generally gravitate towards abolishing institutions that offer them perks at others’ expense. That is an active moral choice. But when you’re groomed to see yourself in relation to a dominant caste, as a member thereof, it’s simple for a desire for agency in a conflict that you’re born on the wrong side of to slip into a desire to control those people most wounded by it. Seeing people of color as poor, unfortunate souls who must be saved, as opposed to comrades in a fight against powers who would deny us all our humanity, subjects them to an objectifying lens. It simply reformulates the logic of domination; it does not abolish it. As someone who writes in favor of abolition, Romulus serves as a reminder of what not to do.

Yet, I cannot credit Romulus and its authors, because I see no evidence they deliberately indict the White savior mentality. The “text,” as I presently read it, presents Rain’s pre-climactic decision to rescue Andy as heartwarming, despite the fact that he wins not one iota of agency. She does not set him free to decide what his “directive” should be: she simply decides that he should care for both of them more. The most charitable interpretation I can scrap together is that the producers don’t understand how liberation works. Not a single liberation movement, be it a movement for Black lives, feminism, labor, queer folk, or anarchism, roots itself in a demand for better treatment. Offering loyalty in exchange for bennies is always, always known as “selling out,” because you’re still just playing the slavers’ game. No, liberation movements are about being rid of your oppressors. Do you think Frederick Douglass would’ve gone back to his former master’s (and likely father’s) plantation if offered to be treated real nice? No—he’d quite literally fought for his freedom with his fists, and there was no way in hell he’d ever give that up.

Make no mistake: Andy ought to have been this film’s protagonist, and the fact he wasn’t, along with the text serving as damn near an apologia for the master/slave mentality, hobbles even the few virtues the film expresses. We’re treated to some beautifully gothic suspense when the movie’s first Xenomorph emerges from its cocoon, and the being born at the end is not something you’d want hanging over your shoulder at night. But even this “new” creature is just a riff on Alien: Resurrection‘s Newborn. Its arrival feels disjointed from the action and overarching themes—and does it really matter when the main emotional arc flirts dangerously with saying that “t3h slavings r ok if u r nice, amirite?”

Why, then, do I consider Alien: Romulus an important film, despite its mediocre composition and retch-inducing themes? Again, it’s in part because Romulus reminds us what not to do. I don’t abide by the Death of the Author doctrine, but neither do I wholly dismiss it. Authorial intent is important, but art’s appeal lies in its ability to catalyze understanding and invention in the audience’s own imagination. It’s innate to the mechanism of art itself, and good artists exploit it for their own ends. Romulus swells, pregnant, with a critique of its own creators’ lack of courage.

However, I can’t help but also examine Romulus in a broader context. Since just before the 2016 election, Hollywood exploded with more films featuring diverse casts, fronting women especially in important roles. Studios took the advice of feminist blog The Hathor Legacy, which mentioned that female-led outfits performed better at the box office, even when they featured lower production values and were of worse overall quality. This led to more diversity in casting (good), but unfortunately the studios also decided this meant that they could continue to skimp on writing, storytelling, and coherent direction. Privately—and it was privately, because I’d placed my career on pause to fight the first Trump administration at the time—I called this tendency “high-concept social justice” to express how Hollywood used the mere idea of adequate representation to shaft the production. Of course, this pissed off bigots aggrieved by the fact movies no longer pandered to them, while anyone opposed to them often vociferously defended these products against any criticism at all, presuming it must imply closet racism, sexism, homophobia or inceldom.

I cannot blame Hollywood entirely for this strategy. Any writer or artist who creates content that might be categorized as “woke” will earn the ire of the “unwoke” mob. I highly anticipate that, as the sort of author who writes about swashbuckling gay swordswoman scientists in alternate-history Renaissance Venice, I’ll get on their shit-list eventually. Rest assured I will use that vitriol against them, because I’d be stupid not to.

But Hollywood exploits representation to dodge legitimate criticism, and often superficial representation at that. Fandom routinely falls prey to this ploy. In 2009, when the Star Trek reboot hit screens, fans judged the movie more on the respect they believed it earned for Trekkies, not the story or whether it embodied the series’s style, tone, or principles. It’s only a short hop from seeing a movie as propaganda for your fandom tribe to judging a film only by whether or not it pays tribute to your political team or social caste. The bigots already do that, so why not do it to them in reverse?

As culture devolves into a pep rally, discourse suffers, art suffers, and the giant mechanical bedbug that is capitalism scuttles on to siphon blood from another vein on the restless psyche of the American “consumer.” I’ve felt far less enthusiastic about a great many progressively-cast works than I’d have liked because of this trend. It dismays me, because I want to be happy to see more nonwhite, nonmale, noncis and nonhet characters and actors onscreen. I want to see more of those characters onscreen, and in my writing I do my damnedest not to default to your Standard White Male. But gratitude proves difficult when it’s used to paper over scripts that suck ass, or cover for unimaginative reboots.3 I don’t think I’ll ever forgive Hollywood for stealing that joy from me.4

Romulus embodies a natural and nefarious evolution of this half-hearted nod to social justice. We have a diverse cast. Most of our protagonists are Asian, Latinx5, or otherwise nonwhite-coded. But such coding doesn’t counteract the film’s fundamental racism regarding Andy. This outing’s “Final Girl” looks lily-white and a White actress, near as I can tell, portrays her. Romulus ticks ethnic diversity boxes, but still destines its characters of color to servitude as tools or to death. And, in true slasher fashion, it punishes the “slut” of the group by mutating her out-of-wedlock baby into a blood-sucking, matricidal alien horror.

In the wake of their loss to Trump, a disturbing number of Democratic leaders and partisans have decided to jettison any pretense of care for immigrants or queer folk. Given their actions, I’d say that Romulus stands as a perfect embodiment of our fetid zeitgeist. It unmasks Hollywood’s interest in diversity as recuperative, not revolutionary; and appropriative, not abolitionist. And it’s foolish to rely on “woke capitalism” for change when capitalism lies at the root of the system authentic wokeness decries.

Romulus demonstrates how Hollywood reduces representation to a bureaucratic ritual. That isn’t enough. Substantive representation affects all aspects of a story. You must question the assumptions of the setting, the themes, the very way you’ve been trained to look at people. You must examine the sorts of relationships you perceive to be natural, and question your loyalty to received cultural standards and knowledge. You can’t accomplish any of this by sending your project to a consulting agency and adjusting for “sensitivity.” I don’t care how many racists whine about Sweet Baby: as good as that firm’s intentions seem to be, and as hideous as their enemies are, they embody exactly the wrong approach to social justice. They exist so privileged creators and powerful firms can outsource having to give a damn about the people they marginalize. It has zero impact on the power structure.

What would affect the power structure is a genuine alternative cinema. A cinema organized in an anti-capitalist fashion, instead of flaunting performative winks at anti-capitalism, as is today’s fashion, to seduce disaffected young folk and maturing Millennials. A cinema that accepts diversity as a premise and guarantees real power for everyone involved. A cinema that cultivates a range of perspectives on how to achieve the better and more equal world we all require, instead of reducing social justice to a tiresome ritual of repeating shibboleths that suppress thought and inhibit action. A cinema that rethinks the business of moviemaking (finance, distribution, the relationship of moviemakers to moviegoers), the craft of it (how much hierarchy does a production need, really? how much structure is expertise and how much is for the suits? how do you collaborate while preserving authorship?), and the fundamentals of the art (who is the audience? is the very concept of “the audience” reactionary? where is the line between the use of identity to describe structural power and recasting your rebellion in terms favorable to the same?).

I’m entirely certain that our present habit of running superficial litmus tests on social media to determine Who Is Really On Our Side will prove indispensable to this cause.

- And yes, it did fall in 1453CE. The Byzantine Empire was still the Roman Empire, called itself such, and fell in 1453. Only the Western Roman Empire fell in 475CE. ↩︎

- Avatar, at least, saw the colonial protagonist leaving his imperialistic society for a rebellious, indigenous one before proceeding to force the colonists off the planet they sought to exploit. Rain would probably have just tried to negotiate better accommodations for them after the company blew up their homes. ↩︎

- It should go without saying that, when paired with an imaginative reboot or sequel, it can amaze. The all-female Ghostbusters movie originally excited me, because gender-flipping the cast struck me as a good way to create a new lineup people wouldn’t immediately see as just shadows of the original. The representation itself carried latent artistic potential, above and beyond the opportunity to address feminist themes. When the producers revealed they wanted to reboot and not continue Ghostbusters, however, I lost interest. If I wanted to watch the old Ghostbusters, I could just watch the old Ghostbusters. ↩︎

- Except for Prey. Prey was fucking amazing. I have no idea how Hollywood shat that ingenious little reimagining out. Its only flaw is that it had just enough courage to make French colonialists villains, but not genocidal Anglo-Americans. ↩︎

- I’m not a huge fan of the term Latinx, but with certain Democratic strategists somehow blaming the use of that word for their shit performance in the 2024 elections, instead of their penchant for stabbing their base in the back and establishing false dichotomies between “identity politics” and “economic issues,” I’m using the term out of spite. Expect me to cycle through the words Latino, Latina, and Latinx as a general collective noun for persons of Latin American extraction, to encourage a certain genderfluidity when conceiving of the archetypal Latinx person. ↩︎