I recently rid myself of my Facebook account, and less than two hours in I feel amazing.

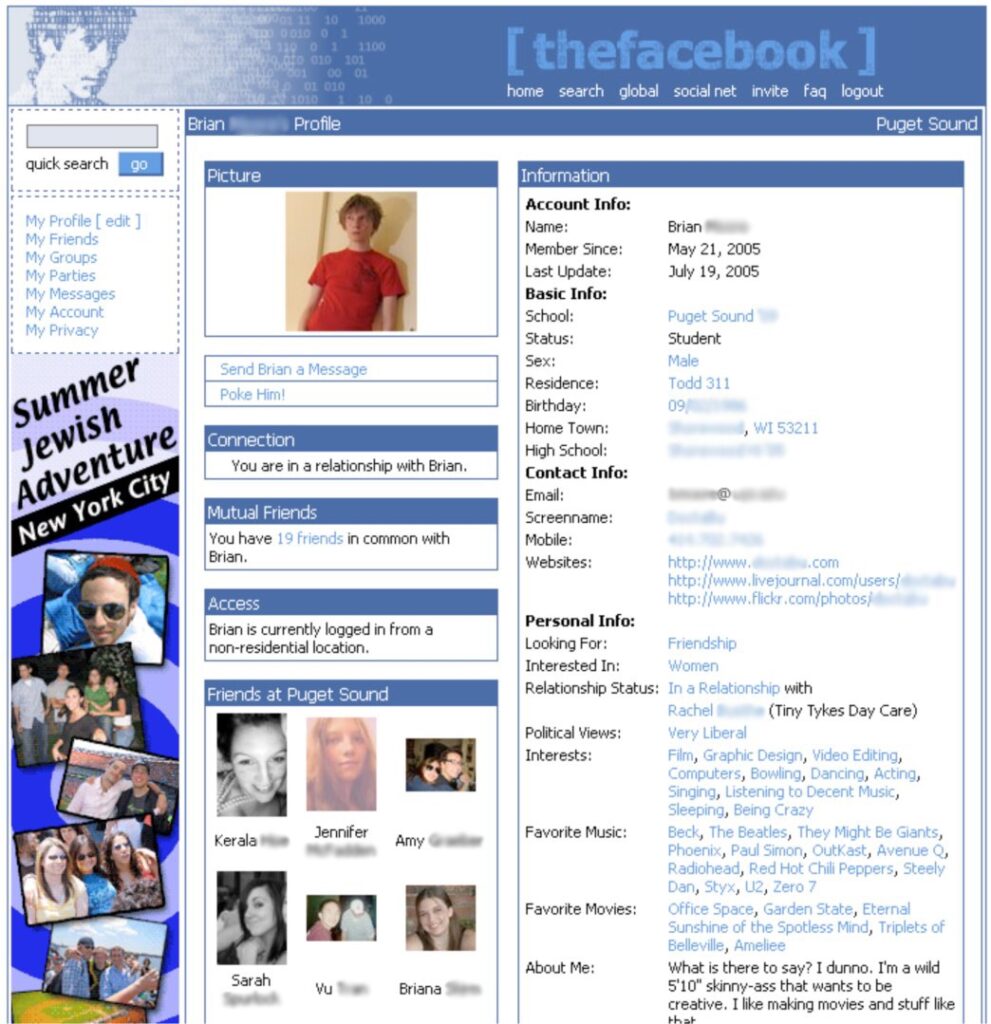

Several times over the preceding months—indeed, over the last several years, though I recall only hazily—I’ve wondered what I actually use that platform for. I barely recall when I first started using it. Was it around 2004, when I was in Sawtell house at Bennington? I associate it with that ruddy little desk I used to work at, in that double I got all to myself because my roommate chose to live in town at the last minute. Or was it closer to 2008? Most of my memories of the early interface look like the appearance it sported around the end of the Bush era.

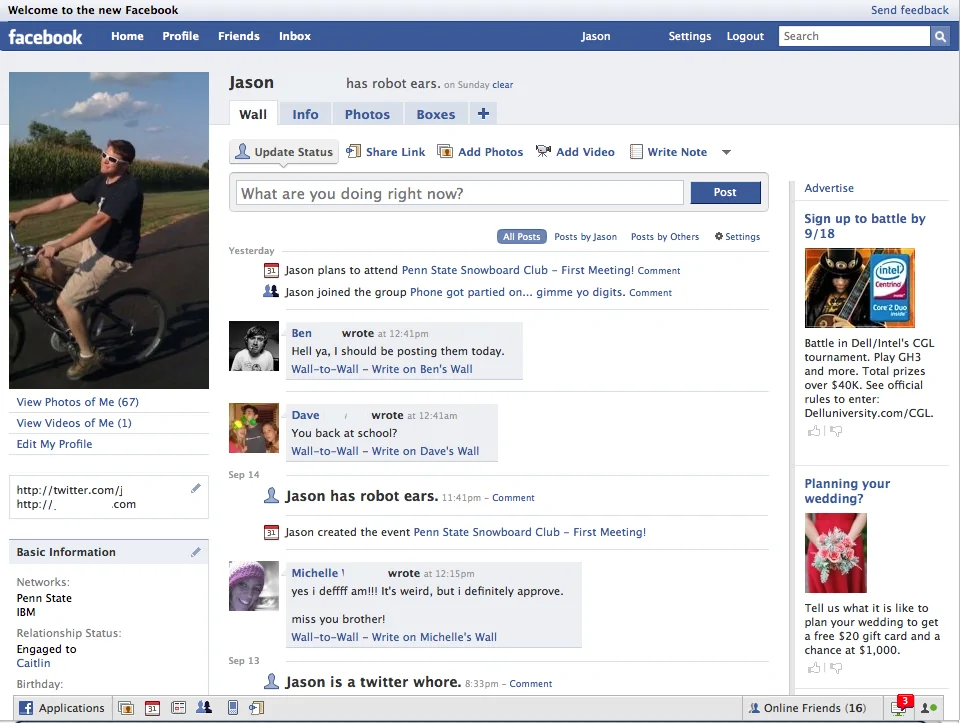

In the early days, Facebook proved a novel way to keep in touch with friends. Your personal wall stood as its centerpiece. The ability to customize that page, to express your interests, desires, and personality through it, carried a certain appeal for early-adult me. When they took that feature away, replacing it with the “feed,” a never-ending train of slop and invective coursing through your mind like a poisoned river, I quietly mourned its loss. Since then, only three things kept me on the site: the ability to instant message friends, the promise of advertising my writing, and sheer habit.

Having spent more than a decade painfully aware of how the platform butchers our attention only to sell it to corporations and governments, and tiring of the deluge of banal content and false community, I’ve considered ditching it for a long time. Writing this, the hypocrisy of keeping a platform for advertising purposes while decrying it for using me as advertising fodder doesn’t escape notice. I’m certain it’s crossed my mind before: I hate advertising, and having to rely on it to survive never sits well with me. I let my HARO (Help A Reporter Out) subscription expire shortly after graduating because the dynamic it encouraged revolting. But I don’t recall how much my relationship to Facebook advertising weighed on my mind. Advertising and marketing tend to be necessary evils when you’re trying to establish yourself as an independent producer embedded in a capitalist society, so I suppose it’s an example of what Bruce E. Levine calls “unavoidable hypocrisies.” In any event, it’s one more reason to get out: one less hypocrisy to manage.

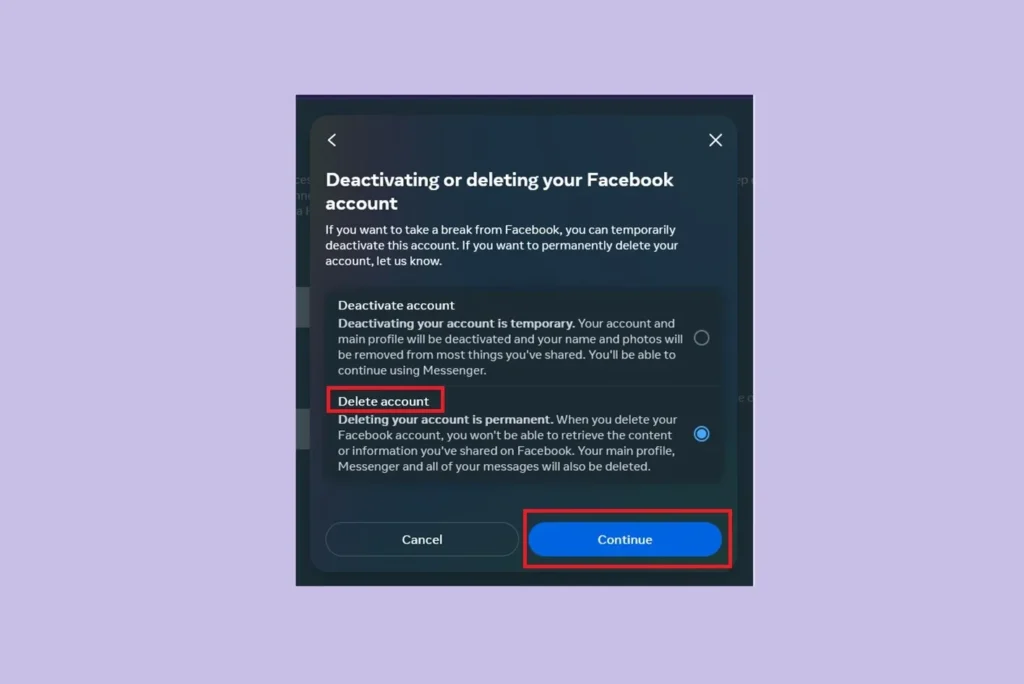

The final straw came when I got into an argument with someone on a left-wing group. It was a petty misunderstanding. I don’t think they were being wholly fair to me, but neither was I being fair to them. I was bitter, lonely, fearfully obsessed with others’ perceptions of me, and I was lashing out. So I got out: out of the conversation, out of the thread, and out of the platform. And while the temptation to go back in still itches at me like a phantom limb, I cannot describe the relief that washed through me upon pressing that terminal button.

Facebook has become nothing but a source of pain for me in prior years. Arguments—some of which ended friendships. Others with strangers I wouldn’t have cared to talk to, and whose opinions I wouldn’t care about, under ordinary circumstances. Some of them might have been important. I do not concur with the conventional wisdom that you cannot persuade others in online arguments. Convincing someone of a perspective almost never occurs instantaneously; it takes time, possibly years. The effects of a conversation you’ve had might never reveal themselves to you, especially if it’s someone who lives halfway across the world, or you never see their face or hear the tone of their voice when you’re talking to them.

The real problem with social media, I think, lies for the reason I stayed for so long, despite the pain: I was looking for status. I wanted to be seen, I wanted standing. It wasn’t a conscious desire, nor one that I would readily admit to given that I am, after all, somebody who views the American tendency to jockey for dominance over every little thing with contempt. I might admit to ambition, sheepishly, as a show of humility and to demonstrate, in good faith, how I sublimate my power drive towards constructive ends. But I would never want to show the public my petty side.

And yet, there it was, on full display. It came out because the understanding that I was on Facebook, a public platform on which I had a public profile and a public identity enmeshed with my social groupings, old, new, and otherwise, rendered me terrified of reproach. I’ve learned the hard way that any opinion online can make you a villain, even to people you largely agree with. By itself, packaging opprobrium and reproach into upvotes and downvotes, likes, hearts, angry little faces creates an explicit measurement of social status, of respect and contempt, optimized to promise objective regard backed with the threat of social damnation. Strip away the emotional context of vocal tone and facial expression, discard patience by demanding brevity and pith, and broadcast every little personal interaction as a public spectacle, and what you have is no longer a “social network,” or even a “social media platform.” What you have is a public pillory for the twenty-first century.

But this stockade isn’t carted out to punish those who have been deemed criminal in advance. It wears an appealing face. People willingly waltz into its clutches, chasing rewards of praise and notoriety, parochial and national. And then, once you’re locked in, the terror of running afoul of other contestants enforces conformity. For a platform that allegedly “individualizes” life and atomizes is, it communalizes individual existence in the most toxic and coercive ways. It encourages us, along with the mutual surveillance of smartphones, to not live authentically but to always imagine the Public, however we conceive of it, as an all-seeing eye judging our every move. And with that spirit haunting our minds at every waking moment, we have no space even for our own thoughts. The imp of Public Opinion demands we all wear masks, and by virtue of social media, that we never remove it.

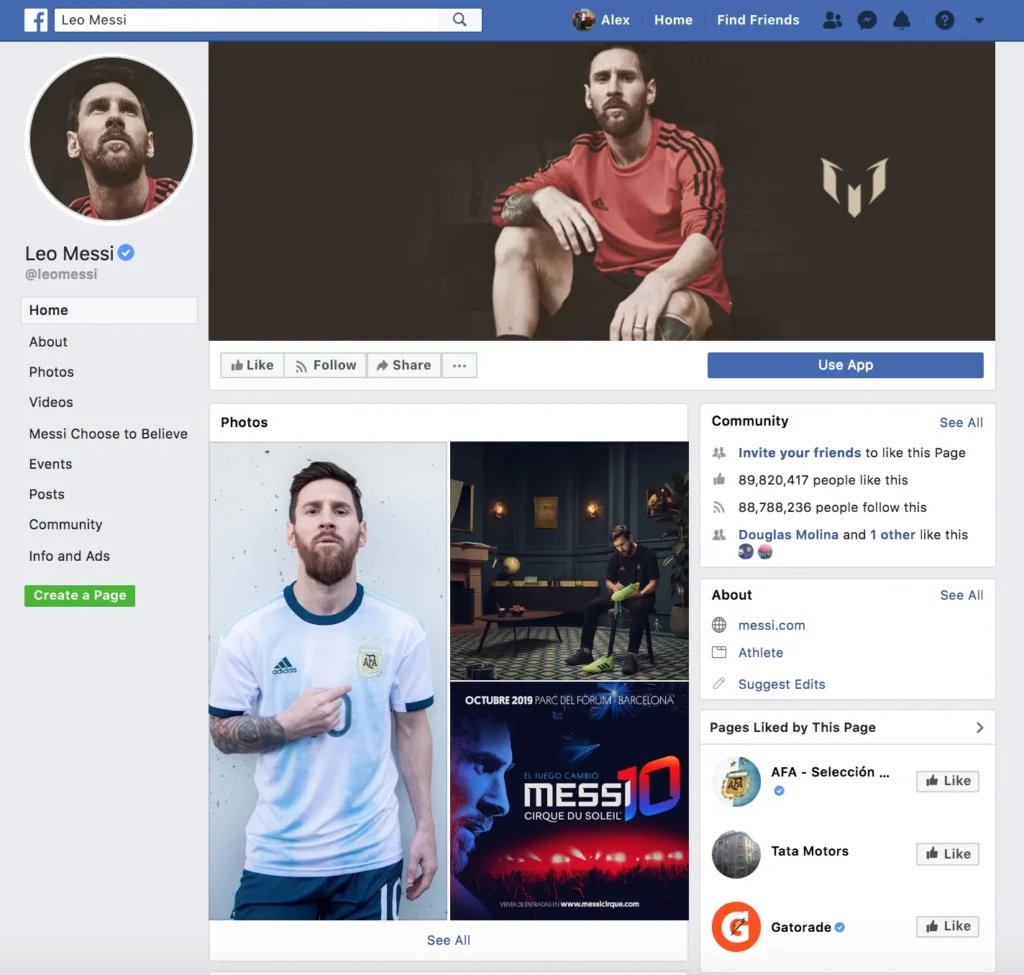

Now that Zuck’s visage-catalog lies, by and large, behind me, I’m substantially freer of that little mephit. Nobody can fully escape the risk of widespread humiliation in the modern age, least of all a quasi-public figure such as myself. But at least, as I shift towards placing this website and self-hosted platforms at the center of my online social presence, I don’t have to accept every invitation to the reputational slugfest. I’m considering Fediverse-based alternatives to Facebook, but now that I’ve left it behind, I’m wondering if I really need anything at all to replace it. I’m not sure an open-source and decentralized Facebook clone actually provides anything of value. If the basic method of interaction is corrupt, and it might be, then perhaps the best option is just to leave it alone.

I’m in no position to leave behind social media entirely. I’ll remain on Instagram and YouTube, since I require them professionally. But I expect my presence here to tend towards precisely that: professional activity, centered on platforms I host alone or that federate with others, and pushing to mainstream networks only as needed to expand my reach. I hope to express myself no less openly than before—indeed, I aspire to be more open and even confrontational, when the situation demands it. But with my personal life no longer such a matter of public record, I expect that security will make it easier not to seek petty confrontation for its own sake.

In an era that demands the illusion of perfection from all of us, the candid display of one’s flawed, unfiltered character is a mark of courage. It is a revolutionary act. I won’t shrink from that challenge. I will, however, not submit that character to examination at the behest of an algorithm. I will express it on my terms, as I please, when I please, and where I please. And it does not please me to sell it on Facebook.